The Thresholds That Have Never Been Crossed

Let's start with what deBoer is actually betting. His conditions include:

- Unemployment stays below 18% (current: 4.3%)

- No single occupational category loses 50% of jobs

- Annual productivity growth doesn't exceed 8%

- The Gini coefficient stays below 0.60 (current: 0.48)

- The top 1%'s income share stays below 35% (current: ~22%)

These aren't just generous tolerances. They're thresholds that have never been reached by any technology in American history. Not electricity. Not railroads. Not automobiles. Not computers.

The highest U.S. unemployment rate in modern history was roughly 25% during the Great Depression — caused by a financial crisis, not a technology. The all-time peak for annual productivity growth was about 3% in the 1930s, after three decades of factory electrification. The Gini coefficient has never exceeded 0.49 in the United States. The top 1% income share peaked at about 24% in 1928.

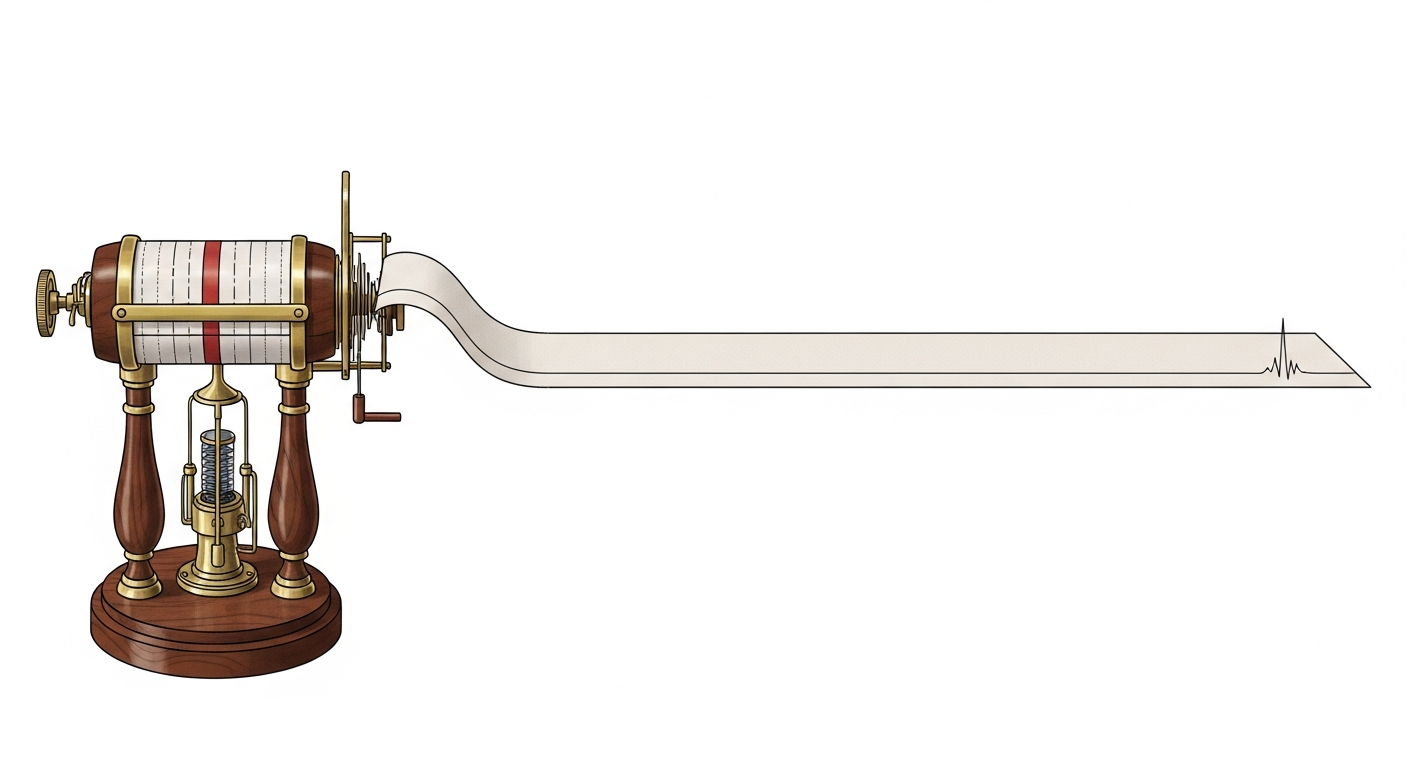

deBoer has set his earthquake detectors to trigger at magnitudes that have never been recorded on American soil. He's going to win because the readings will never get there — not because there's no tremor.

There's one exception worth noting, and it has nothing to do with AI. As Arnold Kling points out, the BLS maintains hundreds of granular occupational categories. Some are tiny. "No single occupational category loses 50% of jobs" sounds generous until you realize a tariff, a regulatory change, or a plant closure could wipe out half the workers in some small category like "textile knitting machine setters" in a single year. deBoer's biggest vulnerability isn't AI — it's a macro shock hitting a micro category. He acknowledged this risk in the original post, but it's the one condition where he could genuinely lose on a technicality that proves nothing about artificial intelligence.

What Every Technology Actually Did in Three Years

Here's the exercise that makes the bet's outcome obvious. Take every major technology in American history and ask: what did it do to aggregate economic statistics in its first three years?

Electricity (1882-1885). Edison opened the Pearl Street generating station in 1882. Three years later? Nothing measurable. Factories were starting to install electric motors, but the economy hadn't noticed. Productivity didn't surge until the 1920s — forty years later — when factory owners finally demolished their old multi-story buildings designed around central steam shafts and rebuilt single-story facilities with distributed power at each workstation. The technology was available in 1882. The organizational restructuring that actually captured the value took a generation.

Railroads (1840-1843). Track mileage was expanding rapidly, but three years into the railroad era, GDP impact was negligible. The full economic transformation — 25% of GDP attributable to rail networks — took 50 years. Employment in railroads reached 2.5% of the workforce by 1880, four decades after the build-out began.

Automobiles (1900-1903). Cars existed but were toys for the wealthy. The horse-drawn carriage industry was still growing. There were 13,800 carriage companies in 1890. Three years into automobile production, zero occupational categories had lost 50% of their jobs. The carriage industry didn't collapse to 90 companies until 1920 — two decades later. The full automobile transition, which created 6.9 million net new jobs and destroyed 623,000, took 40 years.

Personal computers (1983-1986). PCs were on every desk. IT investment was surging. Robert Solow made his famous observation: "You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics." Productivity growth actually slowed. For fifteen years. The resolution didn't come until 1996-2006, when companies that had spent a decade reorganizing around information technology finally started seeing returns. Then productivity slumped back to 1% by 2015.

The pattern is so consistent it's practically a law of physics: technology deploys at technology speed; economies restructure at human speed. The gap between "the technology exists" and "the economy has measurably changed" is 15 to 40 years for every general-purpose technology we have data on.

Three years is nothing.

The J-Curve We're Living Through

Erik Brynjolfsson at MIT calls this the "productivity J-curve." When a major new technology arrives, you'd expect productivity to immediately rise. Instead, it dips. Companies invest heavily in the new technology AND in the organizational restructuring required to use it — new processes, new training, new workflows, new management structures. All of that investment shows up as cost. The benefit hasn't arrived yet. Measured productivity goes down.

Then, years later, the restructuring pays off. Productivity surges. The J completes.

We're at the bottom of the J right now. Seventy-eight percent of companies report using AI in some function. But only 1% consider their rollouts "mature." Only 10-15% are making the deep organizational changes — redesigning workflows, retraining workers, restructuring teams — that Brynjolfsson says are essential for actual productivity gains. The other 85% have installed the electric motors. They haven't redesigned the factory.

This is exactly what happened with electricity. By 1910, most factories had electric motors. Productivity gains didn't materialize until the 1920s. The motor was the easy part. Rethinking how a factory should be organized around distributed power — that was the hard part, and it took 20 years.

deBoer's bet resolves in three years. We're not going to see the top of the J. We're going to see the bottom.

Why "This Time Is Different" Is Exactly Half Right

The AI bulls have a real argument: AI adopts faster than any previous technology. Electricity took 30 years to go from 10% to 80% of factory power. AI went from novelty to 78% business adoption in about three years. No physical infrastructure needed. No wires to run, no tracks to lay, no roads to build. It distributes through existing internet connections at zero marginal cost.

They also argue that AI is qualitatively different because it targets cognitive labor. Every prior GPT — electricity, railroads, automobiles, computers — augmented physical capacity or computational speed. AI directly substitutes for the kind of thinking that knowledge workers do. And it can improve itself: Anthropic reports 70-90% of its own code is AI-written.

Here's where they're half right: adoption is genuinely faster. But adoption is stage one. The bottleneck has never been the technology. It's been the organizational change that follows. And there's no evidence whatsoever that organizations restructure faster in 2026 than they did in 1920. Companies still have hierarchies, job descriptions, contracts, training pipelines, performance review cycles, regulatory compliance requirements, and middle managers who've done things the same way for fifteen years.

Installing ChatGPT is fast. Redesigning how a law firm operates — who does what, how work is reviewed, how partners are compensated, how associates are trained — is slow. It's slow because it involves humans making difficult decisions about their own roles, their own authority, and their own careers. That doesn't speed up because the technology is better.

The leading indicators the bulls cite — junior developer hiring down 20%, software stocks off $300 billion — are real data points. But they're measuring fear, not restructuring. The BLS data tells a different story: total nonfarm employment is at record highs. Professional and business services employment is stable. The macro data that deBoer's bet measures hasn't moved. It won't move in three years. It might move in ten.

The Bet deBoer Should Have Made

deBoer's bet is brilliant rhetoric and bad analysis. He's going to win $5,000 by setting thresholds so extreme they've never been breached by any cause in American history, then declaring victory for the proposition that "AI is normal technology." But winning a bet designed to be unlosable doesn't prove your thesis. It proves you're good at constructing bets.

The interesting question isn't whether the economy stays "normal" by deBoer's generous definition through 2029. Of course it will. The interesting question is what bet would actually test the hypothesis.

Here's what I'd propose. Three tiers, three timelines:

By 2029 (deBoer's timeline): Software developer employment growth decouples from software output growth. Total lines of deployed code increase 3x while developer headcount is flat or declining. This is narrow enough to be measurable and specific to AI's actual capability. deBoer's bet doesn't capture this because BLS occupational categories are too broad and his threshold (-50%) is too extreme.

By 2032 (6 years): Nonfarm labor productivity growth exceeds 3% annually for three consecutive years. Current productivity growth is about 1%. This bet calls for a tripling — which is exactly what happened during the internet productivity boom of 1996-2006, the last time the economy absorbed a major technology. If AI is as economically significant as the internet, we should see this. If we don't, the skeptics have a real argument.

By 2035 (9 years): The ratio of professional services revenue to professional services employment shifts by more than 25% — meaning firms generate significantly more revenue per employee, indicating genuine structural reorganization of knowledge work. This captures the transformation without requiring the catastrophic job losses that deBoer bets against.

These bets test whether AI actually reshapes the economy. deBoer's bet tests whether AI causes an economic apocalypse in three years. Those aren't the same question.

What History Actually Tells Us

The pattern across every major technology is the same:

Years 1-5: Technology exists. Breathless predictions. Early adopters experiment. Aggregate statistics don't move. Skeptics declare victory. (We are here.)

Years 5-15: Organizational restructuring begins in earnest. Frontier firms show measurable gains. Specific occupational categories begin shifting. Productivity data starts to twitch. (Where deBoer's bet resolves — still too early.)

Years 15-30: The J-curve completes. Productivity surges. Industries restructure. New job categories emerge. Old ones decline. The economic transformation becomes undeniable.

Years 30+: Full transformation. The pre-technology economy is unrecognizable. But nobody alive remembers the transition being smooth.

The electricity timeline: Pearl Street Station (1882) → factory motors installed (1900) → factory layouts redesigned (1920) → productivity surge (1920s-30s) → full electrification (1940). Sixty years.

The computer timeline: PC on every desk (1985) → Solow Paradox (1987) → organizational restructuring (1990s) → productivity surge (1996-2006) → productivity slump returns (2010s). Thirty years from installation to peak, and the peak lasted a single decade.

If AI follows the historical pattern — and there's no evidence it won't — then deBoer is right about 2029 and wrong about everything else. The economy will be "normal" in three years. It may not be normal in ten. It almost certainly won't be normal in twenty.

This is where deBoer gets the big picture wrong. He argues the AI hype is psychologically driven — that humans have an evolutionary bias toward believing they live in uniquely important times, and AI flatters that bias. His safer bet is that "the world is going to mostly go on the way that it has."

But it hasn't. Not ever. The world after electricity looked nothing like the world before it. The world after railroads, automobiles, antibiotics, nuclear weapons — none of these were "the world going on the way it has." deBoer is right that AI optimists are at times delusional about the speed. But he's blind to what the historical record actually shows: "normal" technologies are the most disruptive force in human civilization. The printing press was normal technology. It triggered a century of religious wars. The internal combustion engine was normal technology. It killed the horse economy, restructured every city in America, and made possible the mechanized slaughter of two world wars. Normal is not safe. Normal is just slow.

So deBoer wins his bet but may lose the argument. Winning a 3-year bet against economic apocalypse doesn't prove AI is just hype any more than Solow's 1987 quip proved computers were overhyped. The skeptics of 1987 looked right for a decade. Then they looked very, very wrong.

Alexander, meanwhile, makes predictions so vague they can be reinterpreted after the fact. AI companies make claims that are carefully unfalsifiable. Nobody has skin in the game on a timeline that would actually test anything.

The historical record doesn't say AI is overhyped. It doesn't say AI is underhyped. It says everyone is arguing about the wrong timeframe. Three years is too short to see anything. The people saying "nothing is happening" and the people saying "everything is about to change" are both looking at the same data through the wrong lens. One sees the factory with the motor installed and says "see, nothing changed." The other sees the motor and says "the factory will be transformed by Tuesday."

The factory will be transformed. But it'll take a decade or two, not three years. It always has.

What the Markets Say — and What We're Watching

Prediction markets are pricing this roughly in line with the historical pattern. Polymarket gives AGI before 2027 just a 14% chance. The AI bubble bursting by end of 2026 gets 20%. Kalshi has a US recession in 2026 at 20%. The markets are saying: no near-term apocalypse, no near-term singularity. Sounds about right.

Here's what we're tracking:

Prediction 1: deBoer wins the bet. All 17 conditions hold through February 14, 2029. Confidence: very high. The thresholds have never been breached by any technology. Check date: February 14, 2029.

Prediction 2: Software output decouples from developer headcount by 2029. Total deployed code grows 2-3x while software developer employment is flat or declining. This is the canary — the narrowest, most AI-specific metric. Check date: February 2029.

Prediction 3: Productivity growth has NOT tripled by 2029. Annual nonfarm productivity growth will still be in the 1-2% range when deBoer's bet resolves. The J-curve bottom hasn't passed. This is what makes deBoer's win misleading — the absence of a productivity surge doesn't mean AI failed, it means the organizational restructuring hasn't paid off yet. Check date: February 2029, with follow-up through 2032.

Prediction 4: By 2035, we'll know. If AI is a genuine general-purpose technology on par with electricity, nonfarm productivity will have sustained 3%+ growth for multiple years and professional services firms will generate at least 25% more revenue per employee than they do today. If neither has happened by 2035, the skeptics were right about more than just the timeline. Check date: 2035.

Hit reply and tell me: what's the right bet on AI? What metric, at what threshold, at what timeline, would actually change your mind?