Bread and Circuses 2.0: What Rome Teaches Us About a Post-Work Economy

Rome managed mass non-employment for 600 years. If AI takes the jobs, what can we learn from history's one successful experiment?

“The bread is easy. The circuses exist. The missing ingredient is everything else the Romans had.”

— Pattern Lab Analysis

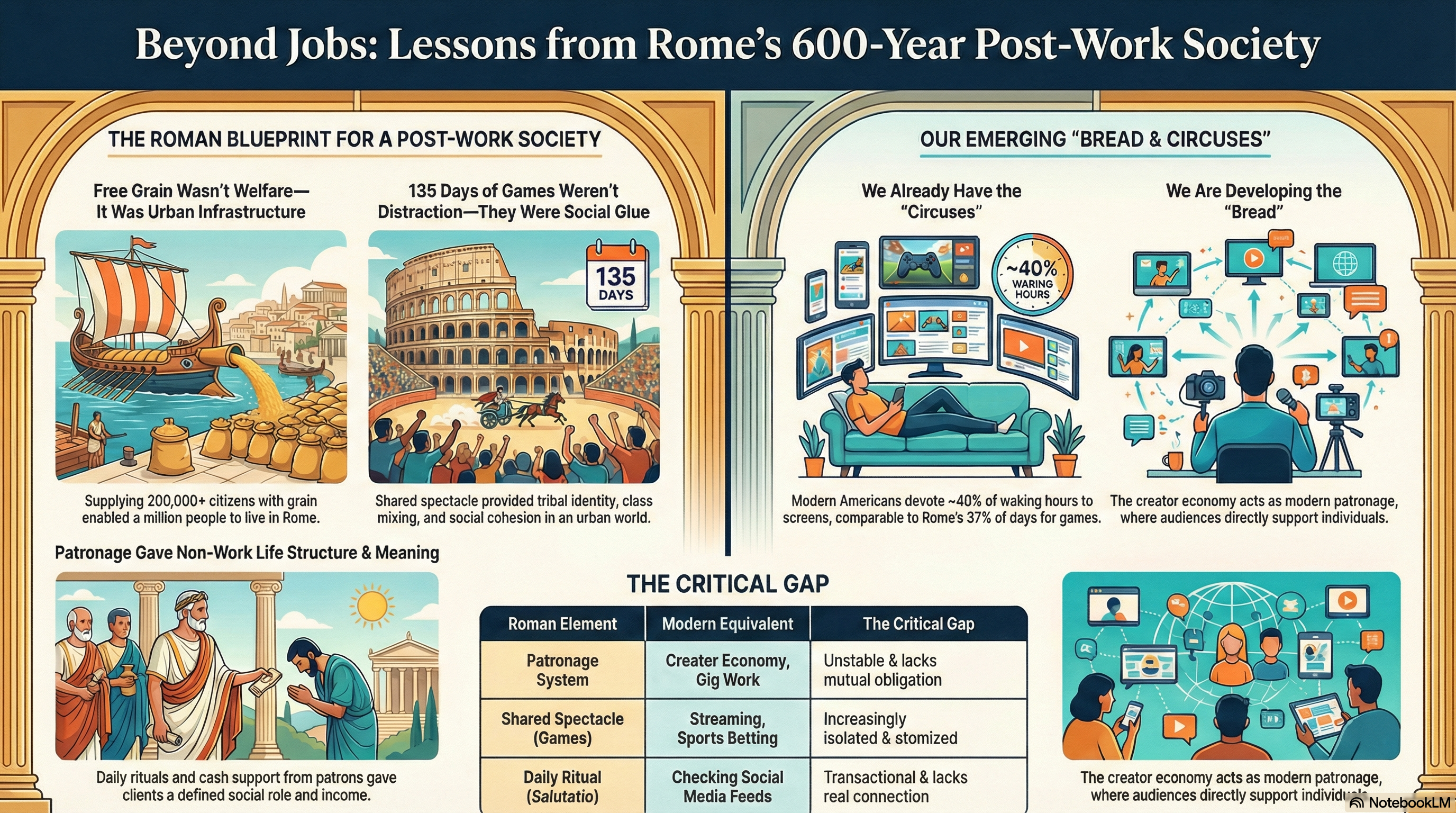

The AI employment debate assumes mass non-employment means social collapse. But Rome sustained a bread-and-circuses economy for six centuries—not as crisis, but as normal social organization. The system failed when supply chains broke, not when Romans got lazy. As sports betting explodes, screen time hits Roman-games levels, and prime-age men leave the workforce, we're already building a modern equivalent. The question isn't whether humans can handle not working. It's whether we can build the social architecture that gave Roman non-workers structure, status, and meaning.

Author's Note

I assign this scenario a very low probability.

I don't believe AI will destroy employment. Every technological revolution in history—the printing press, steam engine, electrification, computers—has created more jobs than it eliminated, often in categories we couldn't have imagined beforehand. I expect AI to follow the same pattern.

But the "AI takes all the jobs" narrative has become so dominant that it's worth stress-testing. If we're going to debate what happens when most humans don't need to work, we should at least examine the one society that actually ran that experiment.

Rome managed a large urban population without productive employment for roughly six centuries. Not perfectly. Not without problems. But sustainably—until external shocks broke the system.

That's worth understanding, even if you think (as I do) that we'll never need to replicate it.

— Alan Pentz, January 2026

The Question Everyone's Asking Wrong

The AI employment debate has collapsed into two camps:

Camp One: Apocalypse. AI automates most human labor. Mass unemployment follows. Society collapses into dystopia, UBI dependency, or revolution.

Camp Two: Emergence. New jobs always appear. We can't predict them, but they'll come. The loom destroyed weaving jobs and created the garment industry. ATMs eliminated bank tellers and banks hired more people than ever. Relax.

Both camps share an unexamined assumption: that mass non-employment is inherently unstable.

But what if it isn't?

What if a wealthy society can sustain a large population that doesn't do traditional work—not for a few years during a crisis, but for centuries?

We have exactly one historical example at scale. And almost everything we think we know about it is wrong.

Part I: The Roman Leisure Economy

The Grain Dole Wasn't Welfare—It Was Urban Infrastructure

In 123 BCE, the reformer Gaius Gracchus passed the Lex Frumentaria, allowing Roman citizens to buy grain from the state at subsidized prices. Over the following centuries, this evolved into the annona: completely free monthly grain distributions to registered citizens.

By the Imperial period, 200,000 to 300,000 adult male citizens received roughly five modii of wheat per month—enough to feed a family. Later emperors added olive oil, wine, and pork. In the 3rd century AD, raw grain was replaced with baked bread, distributed through 254 state-regulated bakeries.

The scale was staggering. After Augustus conquered Egypt in 30 BCE, the Nile valley became so critical to Rome's food supply that its governor was a personally appointed prefect answering only to the emperor. The city maintained 290 granaries and warehouses to store the continuous flow of grain arriving at Ostia.

This wasn't charity. It was infrastructure.

Just as modern cities subsidize highways, water systems, and broadband to enable urban density, Rome subsidized calories. The grain dole made it possible for a million people to live in a pre-industrial city. Without it, Rome couldn't exist at scale.

But the system came with a trap. Once citizens expected free grain, any emperor who failed to deliver paid with his legitimacy—sometimes his life. The annona was both tool and cage.

135 Days of Games: Not Distraction, Social Architecture

At its peak, Rome devoted 135 days per year to public games—more than a third of the calendar.

The Circus Maximus seated 250,000, with another 250,000 watching from surrounding hills. This meant roughly one-third of Rome's population could attend a single event. The Colosseum held 50,000+ for gladiatorial combat and beast hunts.

All expenses were paid by emperors or ambitious politicians. Tickets were free.

The conventional reading is that these games were "distraction"—cynical rulers keeping the masses docile with spectacle while real politics happened elsewhere. Juvenal's famous line about panem et circenses (bread and circuses) is usually quoted as criticism.

But this misunderstands the games' function.

The games were Rome's primary social institution outside family and religion. They provided:

Tribal identity. Chariot racing featured four factions—Blues, Greens, Reds, Whites—that commanded fanatical loyalty across class lines. These weren't just sports teams. They were identity containers in an atomized urban environment where traditional village and clan structures had dissolved.

Status display. Emperors demonstrated fitness to rule through the magnificence of their games. Augustus boasted of giving shows four times in his own name and twenty-three times for other magistrates. The games were political communication in a pre-media age.

Class mixing. Emperors sat in the same venue as common citizens, participating in shared emotional experience. This created a visible connection between ruler and ruled that legitimized the social order.

Shared ritual. In a city of strangers, the games provided common reference points, shared memories, collective emotional peaks. They were the social glue of urban life.

The games weren't what powerful people gave powerless people to keep them quiet. They were what held Roman society together.

Patronage: The Original Gig Economy

Here's the detail most people miss: Romans who didn't work weren't idle. They had elaborate daily structure through the clientela system.

Patronage was the distinctive relationship between a patronus (patron) and his clientes (clients). The patron provided protection, legal representation, business connections, and daily support. The client provided political loyalty, public attendance, and social amplification of the patron's status.

Every morning, clients gathered at their patron's house for the salutatio—a formal greeting ritual. They received the sportula, originally food but later converted to cash. They accompanied their patron through the day's business, demonstrating his importance through the size of his entourage.

By the Imperial period, some observers mocked clients as "greeters" (salutatores) or "toga-wearers" (togati)—parasites who spent their days flattering wealthy patrons. But this misses the point.

The patronage system solved several problems simultaneously:

Daily structure. Non-working citizens had somewhere to be every morning, something to do, a rhythm to their days.

Income without employment. The sportula provided subsistence without requiring productive labor in the modern sense.

Social hierarchy. Status was visible and legible. Everyone knew where they stood relative to everyone else.

Mutual obligation. Patrons needed clients (for political support and status display) as much as clients needed patrons (for material support). The relationship was asymmetric but reciprocal.

Meaning. Clients weren't unemployed—they had a role: supporting their patron, witnessing his business, amplifying his importance. The role had dignity within the Roman value system.

This is what we miss when we imagine mass technological unemployment. We picture purposeless people staring at walls. Romans without jobs spent their mornings at salutatio, their afternoons at the baths, their evenings at dinner parties, and their holidays at the games. They had roles, rituals, and social position—just not "jobs" in the modern sense.

Part II: Why Did It End?

The easy story is that bread and circuses caused Rome's fall. Edward Gibbon, writing in 1787, listed "higher taxation and spending of public monies for free bread and circuses" among his causes of decline. This "libertarian consensus" persists today: welfare made Romans soft; dependency sapped their virtue; collapse followed.

Modern historians largely reject this narrative.

In 1984, Alexander Demandt counted 210 scholarly theories for Rome's fall. The list has grown since. Current synthesis emphasizes:

Supply chain collapse. When Vandal raiders captured Carthage in 439 CE, the Empire lost a primary grain supplier. The annona couldn't function without grain. By the time Rome fell in 476, grain distribution was already "irregular and largely symbolic."

Climate and disease. Twenty-first century scholarship, incorporating archaeology, epidemiology, and climate science, emphasizes the Antonine Plague (165-180 CE), the Plague of Cyprian (249-262 CE), and climate shifts that disrupted agriculture across the Mediterranean.

Military overextension. Defending borders thousands of miles long against continuous pressure eventually exceeded the Empire's capacity.

Economic transformation. The shift from slave labor to colonate (peasant tenant farming), currency debasement, and the breakdown of long-distance trade networks restructured the economy in ways that made the urban grain dole obsolete.

Notably, the Eastern Roman Empire—which maintained the annona in Constantinople—survived another thousand years until 1453.

The scholarly school pioneered by Peter Brown doesn't even accept that Rome "fell." They see gradual transformation from classical to medieval structures, with more continuity than rupture.

The takeaway: Rome's bread-and-circuses system didn't fail because it was unsustainable, morally corrupting, or economically foolish. It failed when external shocks disrupted the supply chains that made it possible. The social technology worked fine. The logistics broke.

Part III: The Modern Bread and Circuses (Already Here)

We don't have to speculate about whether a bread-and-circuses economy could emerge from AI displacement. We can observe it emerging right now—not from AI, but from structural economic shifts already underway.

The Circuses Are Already Here

Sports betting has exploded. The U.S. sports betting industry posted $13.7 billion in revenue in 2024, up 24% from 2023. Legal sportsbooks took nearly $150 billion in wagers. One in five Americans now bets on sports—up from 12% just two years ago.

This isn't a fad. Thirty-eight states have legalized sports betting. Mobile wagering accounts for 80-90% of bets. The infrastructure is permanent.

Screen time has stabilized at Roman-games levels. Americans average 6 hours 40 minutes of daily screen time, with 2+ hours on social media. Gen Z averages 9 hours. Teens spend nearly 5 hours daily on social media alone.

If Rome devoted 135 days per year to games (37% of days), modern Americans devote roughly 40% of waking hours to screens. The time allocation is comparable.

Tribal identity has migrated online. Blues vs. Greens has become political polarization, sports fandoms, online communities, influencer followings. The psychological function—providing identity, belonging, and shared emotional experience—is identical.

The Bread Is Emerging

The creator economy is modern patronage. There are now 207 million content creators globally, with 1.5 million full-time creator jobs in the U.S.—up from 200,000 in 2020. Most don't make a living wage (only 12% of full-time creators earn over $50K), but they're participating in an attention economy where audiences directly support creators through subscriptions, tips, and purchases.

This is the sportula digitized: patrons (subscribers/followers) supporting clients (creators) in exchange for content, attention, and parasocial relationship.

Men are leaving the workforce. 11.4% of prime-age American men are not in the labor force—up from 5.8% in 1976. In 1960, 37 states had fewer than 5% of prime-age men not working. In 2024: zero states.

This isn't unemployment (wanting work and not finding it). It's non-participation (not seeking work at all). Reasons cited include disability/illness (39.5%), caregiving (17.9%), and "other" (31.6%).

UBI experiments show people adapt. The fear that guaranteed income will create mass laziness isn't supported by evidence. Finland's experiment found recipients were happier and healthier, with no decrease in job-seeking. Kenya's ongoing study—the world's largest—found "no evidence of UBI promoting 'laziness,' but evidence of substantial effects on occupational choice." Recipients shifted from wage labor to self-employment and entrepreneurship.

People given bread don't stop moving. They redirect their energy.

What's Missing: The Ritual Structure

Rome's system worked because non-working life had structure, status, and meaning. The modern equivalent is only partially formed:

| Roman Element | Modern Equivalent | Gap | |---------------|-------------------|-----| | Salutatio (morning ritual) | Checking phone/social media | No reciprocal obligation | | Sportula (daily support) | Gig income, creator revenue, family support | Unstable, stigmatized | | Games (shared spectacle) | Sports, streaming | Increasingly atomized (watch alone) | | Patronage hierarchy | Follower counts, online status | No material obligations attached | | Faction identity | Political/fan tribes | Conflict-oriented, not community-building |

The Roman system was relational. Patrons and clients had mutual obligations. Games were attended together. The social architecture created dense webs of connection.

The modern system is transactional and isolated. We consume content alone. Online relationships rarely create real-world obligation. Status hierarchies exist but don't translate into material support networks.

The missing piece isn't the bread or the circuses. It's the patronage—the system of structured relationships that gave non-work life meaning and stability.

Part IV: What This Means

What the "AI Apocalypse" Crowd Gets Wrong

The assumption that mass non-employment inevitably means social collapse doesn't survive contact with history.

Rome sustained a bread-and-circuses economy for roughly 600 years (123 BCE to ~500 CE). The Eastern Empire continued it for another thousand. Constantinople had its own grain dole and its own faction-based chariot racing (with Blues and Greens becoming so politically important they helped overthrow emperors).

This wasn't utopia. There was poverty, violence, political instability, and eventual transformation. But the system didn't collapse because people stopped working. It transformed because supply chains broke, climate shifted, and military threats accumulated.

The apocalypse framing assumes humans need jobs for meaning and social stability. Rome proves they need structure, status, and belonging—which can come from sources other than employment.

What the "New Jobs Will Emerge" Crowd Gets Wrong

The assumption that new jobs must emerge treats historical pattern as iron law. But the mechanisms that created new jobs in previous technological revolutions aren't guaranteed to repeat.

Previous automation:

- Replaced physical labor while humans retained cognitive advantages

- Created demand for human judgment, creativity, and interpersonal skills

- Expanded total economic output, which funded new employment

AI potentially:

- Matches or exceeds human cognitive performance in many domains

- Automates judgment, creativity, and even interpersonal simulation

- Could expand output without proportionally expanding human-labor demand

Rome shows there's a third option beyond "new jobs emerge" and "society collapses": a wealthy society can sustain itself without most people working, if it builds the right social infrastructure.

This doesn't mean we should want that outcome. It means we shouldn't assume it's impossible.

What We Should Actually Worry About

If something like a bread-and-circuses economy emerges—whether from AI automation or continuing structural trends—the risks aren't what we typically imagine.

Not laziness. UBI experiments consistently show people don't stop being active when given basic support. Romans weren't lazy; they were socially engaged in non-employment ways.

Not economic collapse. If productivity continues rising, the economic capacity to support non-workers exists. Rome funded its system through conquest; a modern equivalent might be AI-driven productivity taxed and redistributed.

The real risks:

-

Atomization without community. Roman games were shared experience; streaming is solitary. Roman patronage created relationships; the creator economy creates parasocial illusions. If people don't work together, what institutions create genuine human connection?

-

Status without contribution. Roman clients had a role: support the patron, witness his business, vote his way. Modern follower counts don't confer obligation in either direction. How do non-workers maintain dignity and social position?

-

Tribalism without integration. Roman factions competed at the games but lived in the same city, attended the same spectacles, acknowledged the same emperor. Modern tribes increasingly occupy different information environments with no shared reality. What integrates a society where people don't work together and don't share experiences?

-

Meaning without purpose. Romans had religion, philosophy, and civic identity that provided meaning beyond work. Modern secular societies have largely abandoned traditional meaning-making structures without replacing them. What tells people why they matter if not their job?

The bread and circuses are easy. The social architecture is hard.

Part V: Investment Implications

Connects to the Degenerate Economy thesis: +0%, 14 signals

If a bread-and-circuses economy is sustainable—not guaranteed, but possible—several implications follow:

What's Not a Bubble

Sports betting and gambling may be structural, not cyclical. The Roman games weren't a fad that eventually passed; they were essential social infrastructure that expanded over centuries. If attention-based entertainment serves similar functions, current gambling/betting growth might represent permanent reallocation of time and money, not speculative excess to be corrected.

Entertainment/attention platforms might deserve utility-like valuations. Roman emperors couldn't not fund the games—it was existential for their legitimacy. If platforms become essential infrastructure for social cohesion, their pricing power and durability may be underestimated.

What to Watch

Platforms creating genuine community vs. just content. The Roman games worked because people attended together. Which modern platforms create shared experience vs. parallel isolation? Live sports, gaming with friends, and synchronous content may have structural advantages over on-demand solitary consumption.

Who builds modern patronage infrastructure. Patreon, Substack, OnlyFans, YouTube memberships—these are early attempts at creator-patron relationships. Which evolve toward genuine reciprocal obligation vs. pure transaction? The winner might be whoever figures out how to make sportula feel like relationship, not purchase.

Status systems disconnected from traditional employment. If work stops being the primary source of identity and status, what replaces it? Gaming achievements, follower counts, community roles, credentials? Whoever builds the legible status hierarchy for non-workers captures an emerging social need.

What Could Go Wrong

Supply chain risk. Rome's system failed when grain stopped arriving from Carthage. A modern equivalent might be: what happens to the attention economy if energy costs spike, if AI infrastructure is disrupted, or if key platforms fail? The dependency creates fragility.

Political instability. Roman emperors who failed to deliver games and grain faced riots or assassination. Politicians in a bread-and-circuses economy face similar pressures. The system creates expectations that become impossible to retract.

Class bifurcation. Rome had a small productive/governing class and a large supported class. If AI creates similar dynamics—a small group of owners/operators and a large group of recipients—political economy becomes increasingly zero-sum. The historical record for such arrangements is mixed.

Conclusion: The Question Behind the Question

The AI employment debate is really a debate about human nature and social possibility.

Are humans workers by nature? Do we need jobs for meaning, or just for money? If AI provides the money (through productivity that can be taxed and redistributed), do we still need the jobs?

Can societies cohere without shared labor? Work creates colleagues, shared purpose, common schedules, and mutual dependence. Without it, what holds strangers together in large-scale societies?

Is the jobs-always-emerge pattern a law or a coincidence? Did new jobs appear after previous technological revolutions because humans are adaptable, or because those specific technologies happened to complement rather than replace human capabilities?

Rome doesn't answer these questions definitively. But it expands our sense of what's possible.

A sophisticated society managed mass non-employment for six centuries—not as crisis, but as normal social organization. It required massive logistics (grain fleets, granaries, distribution systems), substantial resources (conquest funding the whole enterprise), and elaborate social technology (games, patronage, shared ritual).

It worked until external shocks broke the supply chains. The social technology itself was resilient.

If AI produces enough wealth to fund a modern equivalent, the question isn't whether humans can handle not working. History suggests we can. The question is whether we can build the social architecture that makes non-work life meaningful, connected, and stable.

The bread is easy. The circuses exist. The missing ingredient is everything else the Romans had: the daily rituals, the reciprocal relationships, the shared experiences, the legible status hierarchies, the sense that even non-workers had roles that mattered.

That's not an economic problem. It's a social engineering problem. And unlike the Romans, we don't have six centuries to figure it out by trial and error.

This piece is part of Pattern Lab's Deep Dives series, which explores historical parallels that illuminate contemporary debates. It connects to our Degenerate Economy thesis tracking the expansion of entertainment, gambling, and attention-based economic activity.

The Pattern

If AI displaces significant employment, the binding constraint won't be economics (we can afford bread) or entertainment (circuses exist). It will be social architecture: the rituals, relationships, and status systems that give non-work life meaning.

Deep Dive Analysis

Chat with this story

Sign in to unlock AI-powered exploration

For people who'd rather understand than react.

More Deep Dives

The Walkman Trap: Why China's Tech Bet Is Japan's Lost Decade All Over Again

Japan didn't fail because its leaders were incompetent—they failed because they doubled down on industrial policy while trapped under America's security umbrella. China is making the same bet, but without the same constraints.

February 9, 2026

The Script That Always Plays Out: Why America's Immigration Enforcement Crises Follow the Same Pattern Every 70 Years

Federal enforcement promises, capacity constraints, selective crackdowns, local resistance where economically viable—the cycle repeats because the underlying incentives never change.

January 21, 2026

Is Protein the New Low-Fat? The $45B Marketing Question

Americans already overconsume protein by 20%, yet the food industry built a multi-billion dollar market anyway. History suggests we've seen this script before.

January 21, 2026

The Government Strikes Back: How Communications Technology and Economic Stress Reshape Politics

From 1848 to 2026: when new communications tech meets economic anxiety, government reasserts itself. Both left and right populism lead to the same destination.

January 18, 2026